This week on The Spectator Film Podcast... Detour (1945) 11.22.19 Featuring: Austin, Maxx Commentary track begins at 16:35

"The whole meaning of Detour depends on the fact that Al is incapable of providing the impartial account of the action which convention leads us to expect in first-person narratives... O'Hara and Marlowe [other male noir narrators] are to be thought of simply as speaking the truth, both about themselves and about the narrative world in general. They may be mistaken, but they never equivocate, and their impersonality is never questioned for a moment. Al's commentary, however, though it is not hypocritical - he plainly believes every word of it - is profoundly self-deceived and systematically unreliable... In fact, Al's memory of the past is in itself a means of blotting it out, and his commentary, far from serving as the clue which leads us infallibly to the meaning of the narrative action, is like a palimpsest beneath which we may glimpse the traces of the history he has felt comepelled to rewrite" (195).

"[Al] has simply concluded this is the way life must be, and the willed (if unconscious) defeatism implicit in his attitude to his blighted career is the first sign of his habitual tendency to attribute his own choices, and their disastrous consequences, to forces external to himself... Ulmer uses these brief, and extraordinarily elliptical, expository sequences to define his hero as a man who lacks all sense of aim and purpose, who is essentially indifferent to everything but what he takes, at a given moment, to be his own interests, and who, above all, instinctively rationalizes his convenience on all occasions, either by absolving himself of responsibility for his actions completely or by providing himself with a spurious but flattering account of his motives" (195-96).

"[Vera] clearly sets out to 'rook' Al in exactly the way he rooked Haskell, who was in turn preparing to rook his own father, but her spontaneous rapaciousness is actually quite different in kind from that of her male antagonists. The most obvious indication of this difference is the hectoring aggressiveness of her manner. Vera is not a trickster like Al and Haskell, and she does not try to deceive, disarm, or win the confidence of her chosen victim. On the contrary, she goes straight for the jugular in order to dispel any illusion that her womanhood makes her susceptible either to physical violence or to seduction. It is not enough for her to present herself as Al's (or any man's) equal... Vera needs to establish that the inequality of the sexes has been reversed, not eliminated, and her every word and action is designed to convince Al that she can do exactly what she likes with him... and to rub his nose in the humiliating fact of his complete subordination to her... Ulmer unmistakably invites us to take pleasure in the comeuppance of this obtuse pusillanimous egotist at the hands of a woman of such formidable wit, energy, and intelligence" (200).

"Ulmer embodies the contradictory concept of the savage, or nonsocial, society in his use of the metaphor of the road. This metaphor recurs frequently in American narratives, and it is almost invariably used to celebrate individual resistance to the constraints of an intolerably oppressive, conservative, and regimented culture. Actually existing American society is seen as an insuperable impediment to the full self-realization of the individual, and the road becomes the last sanctuary of the true American spirit, which can survive only by taking flight from the social world constructed in its name. This use of the road metaphor turns the mythic American ideals on their head. It employs exactly the same terms of reference - heroic individualism and democratic society - but takes the irreversible debasement of the latter for granted and goes on to affirm the former through characters whose refusal to participate in social life comes to signify a rebellious vindication of America in spite of itself. By contrast, Ulmer preserves the connection between individualism and American social institutions established by the original myth, and he uses the metaphor of the road to argue that this connection manifests itself in practice, not as a democracy of heroes but as an exceptionally inhumane and brutal capitalism. Ulmer's road is not a refuge for exiles from a culture in which America's ideals have been degraded; it is a place where the real logic of advanced capitalist civil society is acted out by characters who have completely internalized its values, and whose interaction exemplifies the grotesque deformation of human relationships by the principles of the market. Al, Vera, and Haskell are isolated vagabonds whose lives are dedicated to the pursuit of private goals which they set themselves ad hoc, in the light of their own immediate interests, and who collide with one another in a moral vacuum where human contacts are purely contingent, practical social ties have ceased to exist, and other people appear as mere values to be exploited at will" (204).

This week on The Spectator Film Podcast... Ministry of Fear (1944) 12.20.18 Featuring: Austin, Maxx Commentary begins at 24:00 --- Notes --- We watched...

This week on The Spectator Film Podcast... Strangers on a Train (1951) 12.7.18Featuring: Austin, Maxx Commentary starts at 28:35 --- Notes --- Hitchcock's Films...

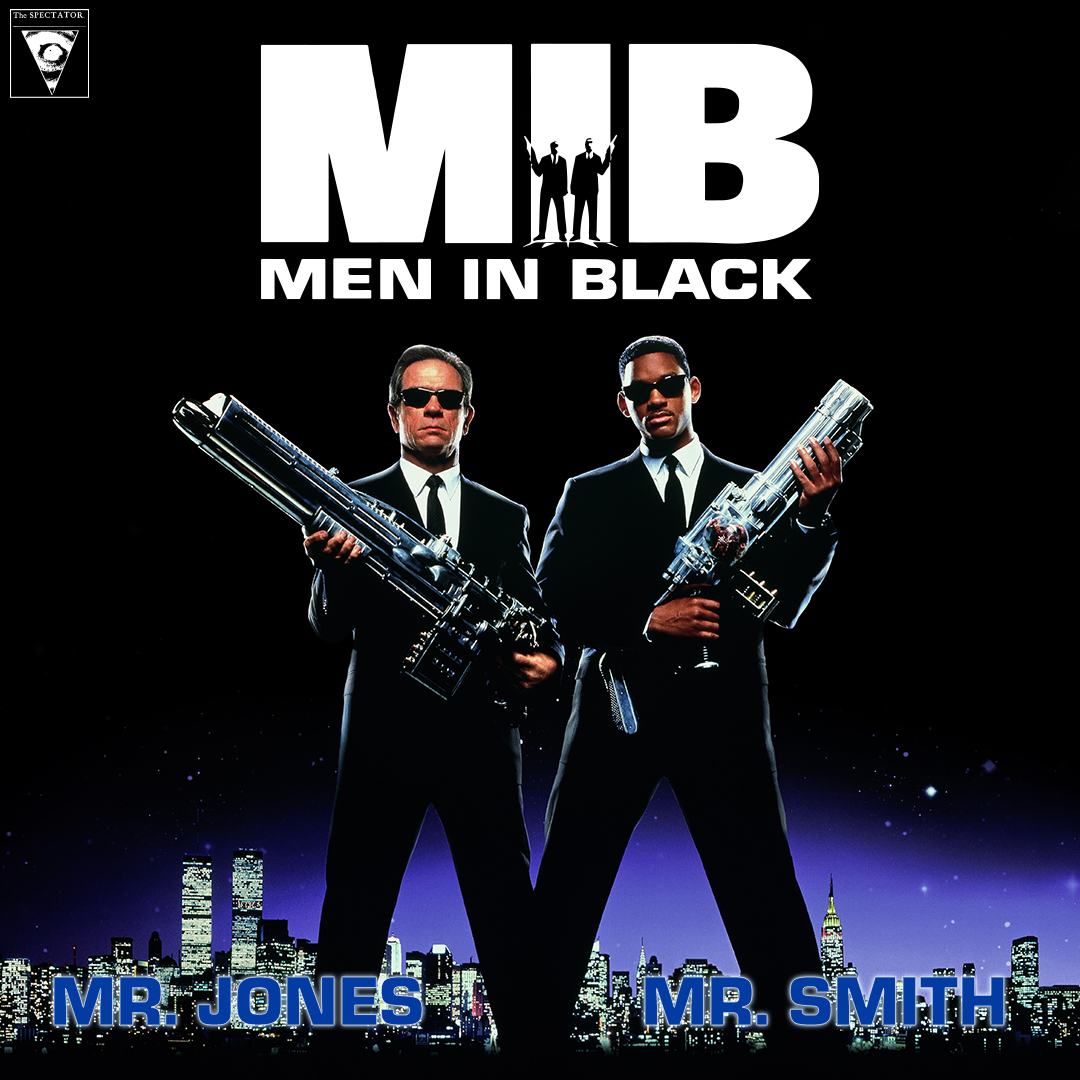

This week on The Spectator Film Podcast... Men in Black (1997) 3.1.19 Featuring: Austin, Maxx Commentary begins at 14:43 --- Notes --- Alienhood: Citizenship,...